Introduction

In this chapter, we identify a range of barriers – social, political, economic, ecological, technological – to women’s achievement of economic empowerment in the context of transitions to low-carbon and climate-resilient development. We explore practical strategies for addressing each barrier, as demonstrated by the GLOW projects.

Some of the barriers and solutions are already widely acknowledged and even explicitly addressed in the Sustainable Development Goals. Others are more novel insights into applying a women’s empowerment lens to low-carbon, climate-resilient development. The Conclusions and Recommendations chapter further below summarises areas that are particularly suited to further piloting, research and organisational learning to advance the linked frontiers of gender equality and climate action.

Promote women to decision-making roles for green economic transitions

Issues

The first issue is that women are commonly excluded from decision-making roles in both family-owned production and small enterprises, as well as external enterprises, collective community and government decision-making. This is true for productive activity at large and equally true for decision-making in the realm of emissions avoidance and climate resilience.

For example, in East Africa, Intellecap describe how women provide the largest share of farm labour. Still, men dominate decision-making, such as how to spend income, what type of crop to plant, and what type of fertiliser and inputs to apply. In some places, women are only allowed to undertake subsistence farming, such as vegetables for food, while cash crops are reserved for men.

In this region, Intellecap found that ‘gender mainstreaming’ is widely interpreted by businesses to mean achieving the ‘mandate of having at least one-third of the workforce as women’ – a requirement that is enshrined in the Constitution of Kenya (2010, article 27). Dig deeper, and you realise that the one-third mandate is being met for labourers employed by businesses. However, in terms of management and company leadership, women are far in the minority.

A similar picture of women’s missing leadership emerges in Cambodia. Here, women and men say they share responsibility for agricultural decisions at the household level. Women tend to be primarily responsible for the household’s finances, making independent decisions about small expenditures and managing tasks such as loan repayment. However, when it comes to public leadership positions outside the household, the dynamic changes.

GrowAsia’s ASEAN green recovery through equity and empowerment project finds that women are 51% of Cambodia’s agricultural labour force, and produce 70% of the country’s food, but are only 24% of household agricultural holding managers, 12% of agricultural extension officers and 10% of agricultural extension services beneficiaries. Sixty percent of agricultural cooperative members and 34% of agricultural cooperative Board of Directors are women. Few women belong to agricultural cooperative committees; when they do, they often fill administrative positions while men take on leadership roles (GrowAsia 2023, page 7).

The second issue is that when climate-resilient development programmes solely or mainly target women and aim to elevate women’s status, there may be pushback from husbands and/or from more powerful community members. Power-holders may feel that their decision-making powers and control are being compromised, and they may feel threatened. This dynamic is well recognised in the broader literature and practice. Some GLOW projects encountered pushback, but not others. It depended on the local context. GLOW projects used various strategies to diffuse pushback, cultivate support for women’s changing roles, and increase women’s leadership in low-carbon, climate-resilient initiatives.

The third issue is that when women are given greater decision-making authority in a formal sense (such as through public appointment), or gain more decision-making authority by default (such as in the diverse contexts where the migration of working-age men from rural areas may leave a dominance of female-headed households), women may lack the capabilities to be fully effective in their decision-making roles, because of the discrimination and exclusion they have previously faced. GLOW projects have investigated the basket of capabilities women need to be effective decision-makers in the context of a changing climate and diminishing natural resource base – and how women’s existing capabilities can be nourished.

Kenyan farmer on mobile (c) Ian Palmer, CIAT

Solutions: Promote women’s influence in decision-making and boost their capabilities to fulfill these roles

Putting women in decision-making roles in public and private sector policy and management is a part of the solution. Climate programmes and initiatives can include ambitious targets for equalising the gender balance of decision-making and leadership positions to enhance women’s voice and influence.

Further, imparting women with the knowledge, skills and confidence to succeed as decision-makers is essential. GLOW research highlighted three dimensions for building women’s capability to succeed in decision-making, management and leadership of low-carbon, climate-resilient development:

- Strengthen women’s climate literacy and their capabilities in the technical low-carbon, climate-resilient aspects of production, logistics, marketing and other value chain activities. Women need equitable access to weather forecast information (on daily to seasonal scales) that can help them manage their productive activities and be informed climate-smart leaders in the face of the increasingly unpredictable and erratic weather that is a consequence of climate change. They also need equal access to information that explains people’s lived experience with climate shocks and stresses in the context of scientific observations, and that describes future climate change trends. To be influential climate leaders, women need to know how climate change affects their sphere of economic activity and how it will affect them in the future. (see figure)

Climate literacy efforts answer these questions

Women also need capacity development in technical knowledge and skills for introducing low-carbon and more climate-resilient practice into existing production systems and/or for innovating and developing new jobs based on climate-smart practices. Depending on the context, appropriate participatory methods for women’s development may need to overcome literacy, time and mobility barriers (when women are available for training or sensitisation; how easily or safely they can reach meeting spaces). Methods should also be designed to capitalise on women’s existing relevant experiences and capabilities in the low-carbon, climate-resilient and ecologically sustainable production spheres, which may hitherto have been under-recognised and undervalued.

The project Promoting women’s empowerment in agricultural value chains for a low carbon transition in Central America has provided evidence to support the establishment and consolidation of a multi-stakeholder ‘green’ alliance to support women leaders. The nascent alliance, termed Iniciativa IXCHEL (materials in Spanish), launched digitally in 2024 with a webinar series that explores multiple angles of women’s empowerment and water and emissions saving in agricultural value chains (for climate change mitigation and adaptation and resilience).

2. Strengthen the capacity of women in management and decision-making roles through improved financial literacy and business skills (as appropriate). Several GLOW projects stressed the importance of deepening women’s business skills in the context of low-carbon, climate-resilient business development. For example, in coastal Kenya, capacity-building for women “not only focus[es] on aquaculture techniques and ecosystem management but also leadership, business management, and financial literacy to enable women to take on more significant roles within the sector” according to Achieng et al.

In Bolivia, ORBITA Business Advisory Services strengthened women-led and women-dominated ecotourism businesses to strengthen their managerial skills, enabling businesses to use information, understand their competitive advantage, access new markets, and make better strategic decisions. Following a recruitment campaign and registration process, the services were provided to 54 enterprises, with at least 75% being female-owned, female-led, or female-worker-dominated. 1

Business skills can also lay the foundations for technical work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and climate vulnerability. The project Empowering women in agricultural value chains for a low-carbon transition in Central America found that, “when studying the activities women do on the farms, we found that very few have administrative records of their production. In this project we are trying to see how we improve environmental sustainability by reducing carbon and water footprints, this is an important limitation because without administrative records, it is very difficult to understand exactly how much footprint is being generated in the sector.” 2

3. Strengthen women’s self-confidence overall. As well as formal ‘skills development’ as such, other activities can generate confidence-building and informal learning opportunities for women, such as women-only safe spaces for sharing information and mutual self-help. In coastal Kenya, forming women-led cooperatives and support groups provide a platform for sharing knowledge, resources, and best practices. In rural Nepal, ForestAction Nepal not only created organised groups of women around ecologically sustainable businesses. They also made it a priority to secure physical spaces dedicated for women where they could store materials and manage business affairs, meet and care for children, so discharging their work and family responsibilities in balance. Peer to peer support is strongly evidenced as being effective in building women’s self-confidence, see also the Box, below, and the section ‘Encourage gender champions, role models and mentors’.

As well as the technical and psychosocial measures to nurture women’s capabilities, as suggested above, climate programmes must mainstream logistical measures to recruit and retain women participants and leaders. Measures may involve providing facilities for nursing mothers, access to sites and materials for people living with disabilities, timing activities to suit women’s availability, and so on. These practical support measures must be budgeted adequately also, as a matter of equity and good practice. They are an essential but partial piece of the puzzle: taking a holistic approach to women’s leadership, including addressing norms that constrain participation and hostile elements of the work environment, is also necessary.

Foster ‘the strength within’

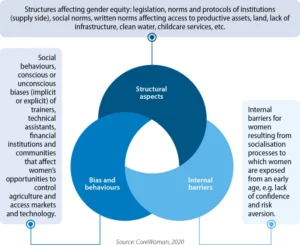

Read moreSystemic approaches are helpful in confronting gender-based discrimination and fostering the empowerment of women. One example used within GLOW is the Corewoman systemic approach. It is based explicitly on the work of Naila Kabeer (Gender Analysis Framework 1996): simplified and repackaged to engage policymakers, organisations and communities. The Corewoman approach has three main facets, as shown in the diagram:

Following from Kabeer’s observations, this approach describes how women may lack confidence due to their social conditioning. They may lack negotiation and communication skills that ‘are a product of socialisation, not biological’ according to Susana Martinez Restrepo, Corewoman co-founder.3 These characteristics can hinder women’s economic participation, leadership and empowerment.

These dynamics can also be further reinforced when institutions internalise discriminatory norms into policies and institutional behaviours – for example, banks may assume which products and information women do or do not want.

Part of the solution, of course, is to nurture women’s psycho-social strength: their self-confidence and willingness to speak up and assert their rights to gender equality. Measures to increase women’s self confidence and ‘sense of the possible’ around their leadership in low-carbon, climate-resilient endeavours are important and highly relevant to climate initiatives and can be included in them.

Strengthening the gender equality and social inclusion elements of all policies relevant to climate action, creating safe spaces and forums for collective action where women can help each other, encouraging gender champions and role models, and confronting toxic and discriminatory beliefs and behaviours are all important components of any holistic toolkit for action, as discussed further in this report.

What motivates women to become land restoration leaders? Lessons from Cameroon

Read moreIn Cameroon, organisations working to empower women through land restoration activities tend to work with farmers groups that have at least 50% women members, as a way of supporting gender-equal participation. They do so together by engaging with traditional and administrative authorities (rural councils).

Despite taking this approach, the project Land restoration for post-Covid rural and indigenous women’s empowerment and poverty reduction in Cameroon found that only 32% of the women in their interview sample held leadership positions in their land restoration groups.

When asked what motivated them to become farm group leaders, 89% of the women interviewed said it was due to their knowledge of the initiative, and 79% said it was because they had a good education. Other factors motivating women’s leadership are the desire for income generation opportunities (68%), matrimonial status (63%) and culture and tradition (63%).

Women said that the factors holding them back from leadership are low education level, low financial capacity and matrimonial status, each mentioned by 21% of women respondents. The research team said they were “not able to elucidate how matrimonial status affects leadership, as the factor had both positive and negative effects. The group structure, the domestic workload and previous experience seem to have little effect on whether women are willing to take up leadership, as more than 60% of the women reported [those factors] as having ‘no influence’ on leadership.”

Women who choose to become leaders do so out of the desire to help others and to contribute to the community’s development (37%) and because they are nominated to the role and agree to follow the group’s wishes (37%). The enhancement of one’s social status is the motivation for some, as mentioned by 17% of interviewees.

The researchers found that women’s desire to acquire new knowledge and skills becomes more important with time. Only 4% mentioned it as a reason for stepping into a leadership position, and 16% mentioned it as a motive for staying in leadership. 4

Mango farmer, Malawi (c) CIFOR-ICRAF

Increase women’s uptake of decent low-carbon, climate-resilient jobs

Issues

Many GLOW projects addressed the situation where women are trapped in unproductive, poorly paid work – such as smallholder agriculture with meagre returns – and do not participate in some of higher-value activities in value chains (see 1 and 2 in the Chapter 4 figure, above).

GLOW research looked at what happens when women are offered training to improve the ecological and economic rewards of their farming, agroforestry and value chain practices.

In general, the barriers to women’s participation in training and in higher-value activities were found to be complex, and highly locally-specific. Barriers include the pressures of women’s unpaid care work and sparse time available, social expectations and/or personal security concerns that limit women’s movement, and in places, the existence of hostile, sexist vocational and training environments (discussed further in the sections on unpaid work and social norms, below).

Barriers also include stereotypes about women’s and men’s roles and abilities that can – often inadvertently – limit women’s access to knowledge, information and economic opportunity. This section looks at stereotypes and how projects have addressed conscious and unconscious biases. It demonstrates how projects have unlocked climate-smart economic opportunities for households languishing in poverty and climate-vulnerable work, and in a fully gender-equitable way.

Solutions: Map the gaps and potentials for women’s participation along low-carbon, climate-resilient value chains

A popular approach used by GLOW projects was to involve women and men producers together in mapping opportunities for women’s enhanced roles in value chains. This is an approach for increasing women’s diversification into higher-paying jobs that were previously more male-dominated, while simultaneously ‘greening’ value chains.

Approaches start with a situation analysis to ground the brainstorming process and assess options and plans. Several projects used a visualisation exercise, whereby producers map out the value chains for different products and the potential financial benefits at each stage. This process asks the questions: What are the different roles that women and men currently play at each step of the chain? What enhanced roles could women play at each step? The follow-on question is: what gender-responsive and gender-transformative actions would be needed to support women’s enhanced roles and economic empowerment at different steps of the value chain and what would be the benefits to them and their families?

The situation analysis is not just about value addition; it is also grounded in assessments of ecological sustainability and climate suitability at each step, as well as an assessment of the market landscape (market access and maturity). It asks: Are the current value-chain activities climate-resilient and low-carbon (such as sustainability of plant cultivation or forest product extraction, carbon and water footprints of industrial-manufacturing processes, etc.)? If not, what options are there for improving the climate and ecological sustainability of the activities along the chain?

An example of taking the mapping approach to gender roles and women’s contributions is the project Prioritising options for women’s empowerment and resilience in food tree value chains in Malawi (POWER). In this action research context, the resilience of tree growing and production to climate stresses is of fundamental importance, and the climate change mitigation value of the ‘trees on farms’ model is well recognised. Therefore, the mapping and visioning exercise along the value chain embodies both women’s empowerment and low-carbon, climate-resilience goals.

After the mapping comes the generation of options for women’s involvement in value addition. Strategies for women’s economic empowerment are often targeted at adding value to raw materials through processing, packaging and handling. But it must not be forgotten that enhancing women’s roles in marketing is essential too, so economic empowerment may also involve women’s improved access to or leadership in developing new markets: women as ‘sustainability communicators and marketers’.

While the mapping and pursuit of higher-value economic-productive activities for women is an important component of women’s empowerment, it is quite narrowly focused on income generation. It must be viewed within a broader concept of women’s economic empowerment, which embodies a range of enhanced capabilities and elements of wellbeing such as time saving (see also Muriel, B. and Romero, D., 2024, ‘Engaging gender equality in the economic-productive sphere’).

Market intelligence has an important role to play in maximising potential for women’s economic empowerment in value chains. So, too, does broader environmental assessment beyond merely climate factors.

An illustrative case is Creating Indigenous women’s green jobs under low-carbon Covid-19 response and recovery in the Bolivian quinoa sector. Researchers assessed the declining reliability of quinoa yields in the high plains region of Bolivia in recent years: a decline which has affected both food security (households’ own use of quinoa) and the income they derive from selling it.

They found that not only are climate factors such as erratic rainfall behind reduced quinoa yields. The international quinoa market has also been largely in flux. New producer countries such as Spain have surged onto the market. International prices of quinoa have been affected by the Russia–Ukraine war.

On the environmental front, intensive agricultural practices meant to increase yields have deeply eroded the fertility and volume of topsoils, year on year. Previously, fields were left fallow to recover between cropping seasons, diverse and complementary crops were grown together, and quinoa production was mingled with llama-raising, which provided manure for soil regeneration. These practices have diminished in favour of intensive monocultures. Reliability of water supply is important for quinoa-growing, but rainfall becomes more erratic with climate change, and infertile soils with little organic matter do not retain water well.

In the context of these intersecting drivers of agricultural decline, the solutions for Indigenous women’s economic empowerment in agriculture are multiple: produce and market quinoa varieties with high nutritional and aesthetic qualities and capitalise on markets for organic quinoa; add value by diversifying the range of quinoa products created – including combining it with other local products such as cañahua, amaranth, cacao, Brazil nuts, and coffee, making quinoa milk and beer, and pursuing holistic agricultural management techniques to enrich the soil and agrobiodiversity for a more robust production system.

Welcoming the municipality team to the village (c) ForestAction Nepal

Solutions: Make alliances with power-holders to increase women’s influence and sphere of activity

One of the most promising approaches for addressing resistance or pushback on women’s economic empowerment programmes was shown to be facilitated dialogues, involving different configurations of male and female stakeholders at nested scales from the household to the community and local government levels.

At the heart of this strategy is the idea of demonstrating through guided and deliberative discussion how everybody in a household or community can benefit from women’s empowerment. Tools that can help with this include facilitated dialogue methods such as those used by Prioritising options for women’s empowerment and resilience (POWER) in food tree value chains in Malawi. The use of such tools also needs to be tested for cultural and situational appropriateness.

The POWER project adapted for the Malawian context an existing methodology known as the Gender Action and Learning System (GALS) and Financial Action and Learning System (FALS), originally developed by Dr. Linda Mayoux. They also borrowed and adapted from several participatory analysis frameworks, including especially Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) to facilitate livelihoods analysis, (Chambers, 1994); the Harvard Analytical Framework to facilitate gender analysis, (March, et.al., 1999) and Kabeer’s empowerment framework to facilitate power analysis (Kabeer, 2021).

The POWER method begins at the household level with participatory tools for head(s) of household, partners, children, and extended family members to examine their current situation and position in the mango value chain, understand how the POWER project interventions might change or uplift their position, and facilitate the family to plan for these changes in a gender equitable way. 5

The method targets the transformation of gender relations in the household and at the level of the mango ‘bulking centres’ (the local area from which mangoes are collected and aggregated to be sold) and district levels. 6 Mentors are assigned to households and mentors lead a process over several months, which unfolds as follows:

“[The process] begins at the household level with participatory tools for head(s) of household, partners, children, and extended family members to examine their current situation and position in the mango value chain, understand how the POWER project interventions might change or upgrade their position, and facilitate the family to plan for these changes in a gender equitable way.” 7

There are ten modules to work through, and each takes approximately two hours. Once all ten modules have been completed, the participants are invited to plan and participate in their own graduation ceremony with other family and community members: “The graduation ceremony provides an opportunity to reflect on gender transformative change with a new generation of POWER champions.” 8

The intervention trialled by the project team was deemed highly effective. They conclude that household members were willing to accept and engage in gender-based and contextual negotiations on how to share planning tasks, leadership on asset aquisition and decision-making around resource use. 9 The POWER team does, however, believe it would take at least five years of implementation for these more gender-equitable approaches to become fully culturally embedded.

Encourage gender champions, role models, and mentors

GLOW projects consistently highlighted the role of gender champions as an effective practice for women’s economic empowerment — as part of a larger suite of measures. In private sector businesses, Intellecap found it essential to designate a champion for women. This person can have responsibility for and drive forward “implementation of the actions and activities that improve inclusion of women in the business and drive the gender agenda for the business” (Intellecap case study, 2024). This means having a designated individual whose defined job is to advance more gender equitable opportunities and outcomes in the business.

Such a person could, of course, be of any gender. Even with a gender champion in place, individuals across the business need to consider gender equality and equity as their mission and foreground it in their everyday work. These principles also apply in the public sector.

Role modelling was another consistent theme. It differs from assigning a gender champion, insofar as role modelling implies successful women entrepreneurs and leaders sharing their experience with new women entrants to the sector who face similar challenges. Mentorship, similarly, implies the moral and practical support of experienced women in the public, private sectors or civil societies, for their less-experienced peers.

Role modelling and mentorship can be effective in informal ways, as well as more formal arrangements. The Bolivian Sustainable Tourism Observatory supported the creation of knowledge exchange platforms for Indigenous women eco-tourism entrepreneurs, which fostered opportunities for informal role modelling and mentorship among them.

Even when such activities are informal, it takes active coordination and funding to arrange and drive such networking opportunities and meeting spaces. In GLOW projects, women’s groups, enterprises and intermediary organisations (such as domestic NGOs) have all relied on grant money to foster role modelling and mentorship activities.

It is hoped that the vital personal connections and inspirations that women have gained will yield legacies of empowerment in the future. In locations such as the rural Nepal example, where women entrepreneurs established actual buildings as safe spaces for women and established local agreements for ongoing use of the facility, it is hoped that these functions will be ‘institutionalised’ to some degree in the future.

Gnetum planting, Cameroon (c) CIFOR-ICRAF

Increase women’s access to productive assets for green economic transitions

Issues

Access to productive assets is a strong, common thread that runs throughout the GLOW findings. Lack of access to productive assets for low-carbon and climate-resilient economic activities is widespread in developing economies. It is commonly documented and recognised that women have far less access to land, finance and agricultural inputs for their economic empowerment than men do. These longstanding dimensions of general poverty and inequality also hamper women’s low-carbon, climate-resilient development.

In East Africa, women’s unequal access to land is an entrenched issue, according to Intellecap. In spite of national laws that allow for equal property rights for men and women, in practice, land is handed down to male children, not female children. Women’s lack of land tenure makes it harder for them to secure credit – so they are doubly disadvantaged.

In Malawi, where the GLOW project targeted women’s empowerment in fruit and macadamia net value chains, both fruit and nut farmers “…rely on projects to source seedlings. Lack of readily available water sources, limited resources to control pests and diseases, and management shortfalls (including organic or chemical fertilisers) have led to the loss of many trees and under-productivity, especially in the case of macadamia. Women, particularly, are more challenged than men, given that they are more financially and labour-constrained. They are also limited in terms of mobility.” (Kampanje et al. 2022. Gender assessment study for improved fruit tree and macadamia nuts value chain in Mzimba and Kasungu districts of Malawi; page 4)

In Nepal, women struggle to access to credit from financial institutions due to the lack of required collateral and onerous documentation requirements. To compound this issue, when women disproportionately lost their jobs during the Covid-19 pandemic, the government’s economic recovery plans seldom reached women engaged in agriculture and small-scale enterprises.

Solutions: Women’s collective action to secure productive assets

Guinean women have successfully used collective action to secure land access, ownership and resources for environmentally sustainable agriculture. In Guinea, a union of women market gardeners and traders, Les femmes de l’Union maraichère de Tangama, acquired 3.5 hectares of land, which had originally been a demonstration plot for a university, for their members’ use. They allocated the land among individual union members, for personal and household use. The smaller parcels have subsequently been handed down from mother to daughter over the generations.

The ability of the women to mobilise productive assets was further enhanced when this union joined a larger union body called the Fédération des paysans du Fouta Djallon: a 750-member body dedicated to horticultural production (of which, 700 are women). Affiliation with this body helped members to access agricultural inputs and key information from the government about production methods. It also enabled them to articulate viable requests for external support. Government agencies, financial and technical partners found that formalised women’s organisations and clearer, more stable land tenure arrangements, were essential requisites for their providing support to women. 10

It was via this collective organising that members were able to access solar panels and irrigation equipment to irrigate their fields. This eased women’s previous hardships, because traditional, manual irrigation methods were very tedious. Association with the larger federation also provided conduits for women farmers to take up leadership positions in the union movement, too: the female president of the Dalaba Union maraichère des femmes assumed a position on the federation’s board and as its general secretary: her position helped secure external assistance for the Dalaba women farmers (see La transition énergétique pour l’autonomisation économique des femmes à travers (…) – Ipar, initiative prospective agricole et rurale).

Savings and loan associations run by women for women or by and for low-income community members are well established in many places as development institutions. They are also instrumental in many GLOW project locations in enabling women’s low-carbon, climate-resilient activities. In the Nepali district of Arghakhanchi, the project Co-producing a shock resilient business ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal recognised that savings and loans associations for women provide multiple, mutually reinforcing, functions. They provide women with cash for agricultural inputs. Savings and loans association meetings also provide fora for women to discuss gender equality and social inclusion matters, including gender-related barriers to development. Such discussions – here facilitated by project staff – have contributed to developing women’s agency, with visible changes in their confidence and engagements in local planning processes 11

Solutions: Change the technology, change the production model

Diffusion of new technologies – illustrated by GLOW projects in East Africa – demonstrates how technologies (both new technologies and revived indigenous and local ones) can overturn production models based on high external inputs and create new models that women can embrace on a more even footing with men. If we think beyond what we have always done, emergent technologies and production techniques in agriculture and aquaculture can produce more outputs, which are also more sustainable outputs, with fewer resources.

Land-sparing and regenerative modes of agriculture and forestry, requiring low external inputs enable women to pursue economically empowering jobs and entrepreneurial growth without recourse to as many productive assets as they may have needed under conventional development. Furthermore, circular economy innovations take what were previously deemed waste materials and make them into valuable productive assets. We see this in the following examples of resource-light, or circular, low-carbon and climate-resilient production systems supported by the Reorienting the private sector to enable climate-smart agricultural solutions to address gender inequalities project.

- “Integrated / controlled production systems such as aquaponics and hydroponics that allow for precise control over environmental factors and help reduce resource wastage, minimise the need for mechanical tilling, reduce pressure on land resources, and promote crop diversification.

- Appropriate land management through recycling of waste to inputs lead to enhanced soil health allowing for carbon sequestration and reducing dependence on chemical fertilisers.

- Efficient water use through sensors and smart greenhouses to reduce dependence of agriculture on rainfall, reduce water required for farming, manage irrigation schedule, and use available water more efficiently.” 12

The project notes that “Value chains, such as organic fertilisers, prove to have greater potential for women’s inclusion owing to the waste segregation aspect which is traditionally undertaken by women. Building greater gender impact in these value chains may lead to increased chances of women’s economic empowerment

Some agri-business models lead to a reduction in production cost, which is inherently more suitable for women farmers given challenges faced in access to capital and inputs.” 13

Indigenous skill for producing sustainable goods (c) ForestAction Nepal

Capitalise on women’s initiatives; but ensure that the most marginalised are not left behind

Issues

Many women have managed to seize the initiative to access low-carbon, climate-resilient technologies and ways of working – even if their control of land and funds and their overall literacy are lower than that of men. In Senegal, IPAR and CECI have documented how women can influence the purchase of solar equipment by or with their husbands, or they can purchase it directly if they are widowed and divorced and have the funds to do so. Women farmers are managing to access and use solar panels to drive greater yields in horticulture. They deploy the solar panels and linked pumps and irrigation systems to save considerable time and labour compared to previous manual irrigation methods (workload decreasing from 7.7 hours to 7 hours per day), and their average horticultural incomes have jumped from $1,165 to $2,541 per year.

However, there are distinct groups of women with different levels of empowerment even in seemingly homogenous communities and each group needs different forms of support. Among the communities engaged by IPAR Senegal and CECI, female solar power users are comparatively more educated and confident than non-users. 14 Widows tend to have access to and use solar irrigation technologies. The data on married women is mixed: although most of them say they can influence household spending decisions, most of them also say that solar panels are ‘controlled’ by husbands. In polygamous households, access to solar irrigation technology is heavily defined by one’s rank and status: it is the first wives who are more likely to have access to solar panels, not the second or third wives.

In Malawi, a similar picture emerged. Older and widowed women have more autonomy, whereas young women face further barriers in accessing land and technology because family members think they will marry and move away anyway. According to Kampanje et al (2022):

“Household-level land and tree ownership and decision-making is male dominated, but this gender inequality varies across communities and households depending on factors such as marital status and age…. We also found that the older the woman, the more decision-making authority and autonomy she has. Widows who have retained access to land from their deceased husbands, as well as older divorced women who have been allocated land in their home villages, have relatively more decision-making autonomy, and have significantly higher tree tenure security as compared to their younger counterparts.” Younger women are expected to get married and move away. Married women may have access to productive assets through their husbands but it is ‘conditional’”(Kampanje et al. (2022), Gender assessment study for improved fruit tree and macadamia nuts value chain in Mzimba and Kasungu districts of Malawi; page 4.).

It is natural that there is diversity among women and that some are more able to capitalise on the opportunities of low-carbon, climate-resilient livelihoods and economic empowerment than others. However, what strategies are there for identifying and nurturing the capabilities, assets and empowerment of more marginalised women and indeed, other left-behind social and socioeconomic groups? GLOW project findings suggest that the following options are worth considering.

Solutions: empower women with ‘mobile’ skills when needed

GLOW research has suggested tailoring capacity development to specific groups of women based on their intended life trajectories and the sociocultural opportunities and constraints they are likely to face; for example, by empowering young, unmarried women with technical, life and business skills that will ‘travel well’ with them when they marry.

In patrilineal settings, young women may be considered temporary residents because they will move to their husband’s home. Young single women can be empowered with “mobile knowledge assets that they can use regardless of where they relocate to” (Kampanje et al. 2022. Gender assessment study for improved fruit tree and macadamia nuts value chain in Mzimba and Kasungu districts of Malawi, page 9.).

This approach recognises that even while climate initiatives can and should confront discriminatory power structures and inequalities now, it can take a long time to shift deeply embedded social norms. Initiatives can therefore adopt women’s empowerment strategies and tactics of this kind which both:

- Empower women in the near term (in the context of existing male-biased inheritance systems, culture and the limitations for women regarding land access, tree tenure and agency).

- Contribute toward the longer term shifts in discriminatory social norms toward de jure and de facto gender equality.

Solutions: Social protection to address shocks and extreme poverty

It may be necessary to design and implement social protection supports for the poorest and most heavily disadvantaged women, who do not have the wherewithal to participate immediately in training and capacity development because they live in extreme poverty or destitution. More extended intervention periods involving more partnerships among government agencies, community-based organisations and/or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) may be desirable or necessary for such women to graduate into more stable livelihoods, including green jobs, and higher living standards.

The need also arises in respect of women workers’ healthcare needs. GrowAsia found in Vietnam that many women farm labourers’ health and safety needs are unmet. They strongly recommend that the government extends workers’ access to social insurance (state programmes to protect people from financial hardship arising from unavoidable situations such as loss of earnings during illness, injury, disability and old age); also, that businesses and workers consider increasing their social insurance participation. (GrowAsia, 2023, page 15).

Agriculture mobile app use, Nepal (c) SIAS

Increase women’s access to markets for their eco-friendly products

Issues

Opportunities to develop supply chains are a crucial strategy for many developing country governments, including in the context of national just transition and climate strategies. Some constraints on low-income farmers’ entry into markets and supply chains are gender-neutral as such. For example, in Cambodia, farmers with contracts to supply supermarkets and vegetable shops “struggle to produce vegetables that meet the required minimum standards in terms of size, appearance, and weight due to limited agricultural technology and knowledge and difficulties adapting to variable weather conditions” (GrowAsia, 2023; page 7). Further, some equipment to help farmers adapt to unreliable weather is readily accessible and affordable; other equipment less so. In Cambodia, drip irrigation is affordable and readily used as a water efficiency measure to sustain crops. However, net houses (structures with agricultural nets that create micro-climates to nurture plant growth) are far more expensive, and farmers rely on NGOs to subsidise their access to them.

In other cases, barriers to entry in commercial farming have a more gendered aspect: in Cambodia, women farmers without a male partner find it difficult to operate heavy farm machinery to enable them to operate at greater efficiency. GrowAsia highlights the importance of disseminating more women-friendly climate-smart technologies as a way to increase financial inclusion (GrowAsia, 2023).

In other contexts, such as parts of Africa, Latin America and South Asia, women’s lower literacy rates, lower access to information, training and ICTs have definitively hampered women’s access to markets compared to their male counterparts. For example, although most farm labourers in East Africa are women, the suppliers in the value chain are men.15 Women’s improved access to digital technologies (both to enhance women producers’ knowledge and access to supplies, and for marketing of their own goods and services) and collective action by women through producer cooperatives and federations emerge as two effective strategies to address these barriers.

Solutions: Link women to markets digitally

Linking women farmers, traders or customers to high-quality production inputs and to more extensive markets for their goods and services online – via digital platforms – can reduce vulnerabilities and improve opportunities for women in value chains. It means they side-step middlemen. This has been demonstrated powerfully via the Reorienting the private sector to enable climate-smart agricultural solutions to address gender inequalities project in East Africa. For example, the project has promoted aggregation and technology platforms, which provide farmers with real-time climate data and access to marketplaces to better manage cropping schedules, reduce post-harvest losses, and build their resilience to climate-related market fluctuations. 16

In Nepal, work by the Co-producing a shock resilient business ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal (CREW) project investigated the current uptake and the potential for women farmers to use mobile phone apps to access weather and climate information (which supports climate-resilient production) and to connect with market data to support trading.

The project finds that, to date, gender biases and barriers have disproportionately deprived rural women from using and benefitting from digitalisation. Digital gender gaps occur in three connected ways in rural Nepal:

- unequal access to available digital technologies and infrastructure

- women’s limited knowledge, at present, of how to use the technology; and

- a dearth in development of women-friendly mobile apps especially given low rates of women’s literacy.

There is an opportunity to turn this around with actionable, achievable goals in digital policy that address the intersectional realities of women in rural Nepal.

The research looked at how many women use apps such as Smart Krishi, which enables farmers to connect with experts, and obtain agricultural market data and weather updates. A quantitative survey of more than 350 women farmers revealed that although they are familiar with the use of banking apps, and somewhat familiar with the use of digital technology to access relevant market information, they are barely exploiting the potential of apps to support climate-resilient agricultural livelihoods. Fewer than 5% are using digital technology specifically intended for agricultural information.

Despite constraints, survey respondents agree on the indispensability of digital technology. Over 95% said they had not received any training related to apps designed for agriculture at the start of the intervention. Still, a significant 63% reported they could maximise agricultural output by adopting digi-tech in the future.

Some infrastructural barriers to women’s uptake exist, such as poor mobile phone signal in parts of rural Nepal. Other barriers are of a more sociocultural type, such as the woman who said, “My husband sends remittance money to my father-in-law who then spends it at his will. I am scared to ask for money to purchase a suitable phone”. This speaks to social norms (see below) which can be addressed explicitly in low-carbon, climate-resilience initiatives but take time to influence. The 30% of women in the survey who described themselves as heads of household were more likely to report that they also have financial autonomy, and the autonomy to use digital technology.

Use collective action to secure market access

Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the power of collective action – through associations and federations of women producers – for accessing information and productive assets for climate-smart agriculture. Associations come to the fore again as a way of securing market access for producers.

The project Empowering women in agricultural value chains for a low-carbon transition in Central America studied cocoa and tomato value chains in three countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua. The rationale for choosing these was that they offer the potential for ‘greening’ and also for enhancing women producers’ incomes as they are not subsistence crops but geared toward domestic markets in the case of tomatoes, and export markets in the case of cocoa. The researchers found that the proportion of farmers selling to more formal markets is much higher in Nicaragua (almost 80% of producers interviewed). It is much lower in the other countries, by comparison (close to 10% of cocoa farmers and between 20 and 30% of tomato farmers). Producers with access to more formal markets are more likely to raise their incomes.

Three key factors stood out as instrumental in enabling market access in Nicaragua compared to the other two countries, noting that gender was not a significant differentiator and that these factors applied equally to women and men:

- Having enough land to make the activity profitable increases the probability of selling in a more formal market almost three times.

- Having received training doubles the probability of selling in a more formal market.

Belonging to an association increases the probability almost seven times. On this last point, Nicaragua separates itself from the rest: while in that country more than half of men and women belong to a producer organisation, in El Salvador and Guatemala, less than 20% do so. The percentage of producers who have received technical assistance is also higher in Nicaragua. 17

The detail of an agricultural association’s activities matters – it is not merely a question of ‘whether to associate’. For example, it matters whether an association is skilled in negotiating good purchase deals for its members’ produce. Associations are effective when they can exercise collective bargaining power for smallholders and so give farmers more influence than they would have had as individuals. 18

Use climate initiatives as a way to address discriminatory norms

Issues

Addressing discriminatory norms against groups of women and marginalised people stretches wider than climate action alone and cuts across all facets of sustainable development. However, changing social norms should be viewed as, and financed as, an integral part of climate programming. Until now, such work has not been perceived as relevant to climate action. Donor and governmental programmes and businesses have tended to exclude work that intentionally seeks to combat gender-discriminatory or harmful social norms, considering it less relevant to climate action. In fact, it could not be more relevant. Addressing discriminatory norms calls for a dedicated budget and human resourcing, because harmful norms are holding back women and girls from participating in effective climate action. Here ‘human resourcing’ means both dedicated expertise and training in combating harmful norms more broadly across project implementers.

Examples of discriminatory norms that hold back women from participation in low-carbon, climate-resilient activities in the GLOW study countries include:

- In Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador, smallholder women farmers have been invited in equal numbers with men to participate in training programmes to reduce the carbon and water footprint of their production systems. The incentives to participate are strong: uptake of the new methods saves resources, and therefore enhances household revenues. Despite this, trainers are told ‘women don’t want to come’ (Margarita Beneke in CDKN COP28 video). After further investigation, the training team found out that common social perceptions are that women are ‘not tomato farmers’ (even though women do actually grow tomatoes) and that they face harassment in the workplace including sexual and sexist jokes.19

- In Nepal, there are longstanding taboos around menstruation, particularly among certain castes. These norms hold that when women and girls are menstruating they may not touch people, food and items in the usual way. 89% of Nepali women report their movements being restricted during menstruation, including being forbidden from moving around the community or the home. This creates obvious barriers to women’s ability to engage in economic activity, as well as affecting their social lives and physical and mental health.

- In coastal Kenyan communities, social norms are that women cannot go to sea and women should not swim. However, this is holding women back from participating in environmentally sustainable and economically lucrative new production technologies such as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture.

Solutions: Design climate programmes to engender community acceptance and support for women’s changing roles and actions

Climate programmes and initiatives can be designed so that some of the underlying ‘normal’ beliefs and behaviours that constrain women’s productive involvement in low-carbon, climate-resilient livelihoods are explicitly contested, confronted and addressed.

Approaches to addressing such beliefs should be location-specific and institution-specific. They should be sensitively handled by embedded gender champions and their gender allies, so that initiatives protect the welfare of women and girls in communities and/or value chains and promote positive changes by demonstrating women’s and girls’ abilities.

For example, in the coastal Kenyan communities described above, social norms preventing women from learning to swim constrained their involvement in new, low-carbon, climate-resilient blue economy jobs. The Blue Empowerment Project has been trying to facilitate swimming lessons for women who are eager to take up the new technology; and has supported the creation of women-only cooperatives and local platforms as places for mutual self help and support.

The Empowering women in agricultural value chains for a low-carbon transition in Central America has been working with companies that off-take, process and distribute tomatoes and cocoa from suppliers in the three target countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua. Part of the work is around identifying opportunities for reducing emissions through energy efficiency and renewable energy use in value chains, and for reducing water use, to contribute to climate resilience. They have also undertaken gender analyses to establish whether women experience supportive or hostile work environments. The analyses have led to tailored training interventions for members of both the larger corporate teams and the tomato and cocoa marketing cooperatives that address (among others):

- identifying and halting microaggressions against women in the workplace

- designing projects from a gender perspective

- understanding and embracing notions of positive and co-responsible masculinities

- using inclusive communication and language

- (for women) socio-psychological coping skills. 20

In this way, climate programmes and initiatives can be the vehicle for modelling and advancing positive, gender- and socially equitable norms in women’s and men’s workplaces, potentially generating positive spillover benefits into other walks of life.

Strengthen enabling policies

Issues

Countries’ national climate plans, the NDCs, were first created and submitted to the UNFCCC in 2015–16 when the Paris Agreement came into force. Countries again submitted their enhanced NDCs with greater climate ambition in 2020–21. There was a significant jump in the mentions of women and gender between the first and second rounds. A keyword search by IUCN (2021) found that 40% of the first round of NDCs submitted by Parties to the UNFCCC in 2016 mentioned the word ‘gender’, almost double that proportion (78%) of the new round of enhanced NDCs submitted by 2021 mentioned ‘gender’ (Dupar and Tan, 2023).

NDCs often fail to centre equal rights and intended benefits for women and disadvantaged groups, to the extent necessary. Many countries still need to strengthen the social inclusion element of their climate laws and policies.

In addition to climate policies, countries must also strengthen the gender and social dimensions of related sectoral laws and policies that relate fundamentally to climate action, such as land management and tenure laws, green jobs and skills policies.

For example, in Cameroon, land restoration policies do not sufficiently support women’s needs. The project Land restoration for post-Covid rural and indigenous women’s empowerment and poverty reduction in Cameroon finds that: “…while national policies and policy instruments are not gender-discriminatory, there is room to make them more gender-sensitive and transformative, especially with regards to access and control over resources, access to information and knowledge and lastly, participation, status, and power. Second, more inclusive approaches are needed to make sure people, including women and minority groups, receive up-to-date information and training on context-specific and gender-sensitive land restoration options” (Degrand et al., 2024).

In Kenya, the government has ambitions to develop the ‘Blue Economy’ sector. However, as the government itself highlights in its five-year strategy, women are under-represented: “Currently, the Blue Economy sector is highly dominated by men with very low uptake of maritime professions by women. For this reason, there is need to develop and implement appropriate laws, policies and framework to increase women participation in the Blue Economy Sector” (Government of Kenya, Sector Plan for Blue Economy 2018-22).

It is a partly a question of women’s having inadequate job opportunities in the blue economy sector. It is also a question of women’s existing contributions being invisible or vastly under-recognised because their work is informal and precarious, which leads to their concerns being eclipsed in government policies.

Strengthen the gender and social equity dimensions of climate policies and of relevant sectoral and economic policies

Ultimately, women’s economic empowerment calls for a ‘tapestry’ of enabling policy and regulatory measures, which are consistent, coherent and mutually aligned. They should include full integration and application of a country’s gender equality laws at the sectoral level.

The project Land restoration for post-Covid rural and indigenous women empowerment and poverty reduction in Cameroon undertook a systematic gender analysis of the policies related to land restoration. They utilised using the Havard analytical framework to evaluate whether national policies were gender blind, sensitive or transformative with regards to women’s:

- access and control over resources

- access to information and knowledge

- participation, status, and power.

The researchers assessed three general development strategies or policies, such as the National Development Plan, together with nine thematic policies related to land restoration in Cameroon or that address general environmental issues with links to land restoration. Of the twelve policies: “Results show that more than half of the policy or instruments were gender-blind on all the three criteria of empowerment. In four of the cases where they were gender-sensitive, in at least two of them they were gender-blind. In other words, only two out of the 12 policy instruments were gender-transformative, meaning that much work needs to be done to make our existing policies gender-sensitive and transformative with regards to access and control over resources, access to information and knowledge and lastly participation status and power.” 21

A review of multisectoral policies (agriculture, forestry, climate change and socio-economic) and experiences on the ground, done as part of the Co-producing a shock resilient business ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal project, found that the constitutional provisions and broader, sectoral policy frameworks in Nepal are quite progressive in terms of ensuring the rights and entitlements of women and marginalised groups and have some level of provisions/subsidies for women farmers. However, these seemingly progressive policy provisions are not effectively translated into practice. The findings show that policy distortions start from gaps in developing sectoral regulatory instruments and institutional mechanisms, developing implementation guidelines, preparing required programs with adequate budgets, channelling resources to the target population, actual implementation on the ground to monitoring and evaluating such policies and programs and policy incoherence across sectors.

Integrating gender equity measures in climate and relevant sectoral policies requires multiple interventions. It needs champions within the legislative and executive branches of government, and engagement with relevant stakeholders in society. However, strong analysis of this type can provide a fundamental springboard towards policy change.

Community workshop, Kenya (c) Intellecap

Implement gender equality goals and commitments

Issues

Even when gender equality legislation is strong and is well integrated on paper into climate and related sectoral policies, it may not be implemented in practice. This is the case in Nepal, where the constitution and national laws for gender equality are strong. The high-level political commitment to gender equality carries through Nepal’s NDC, which GLOW has flagged as one of the most progressive NDCs for women. There is a legal requirement for local governments and institutions governing the use of natural resources (such as Community Forest Users Groups) to be comprised equally of women and men. Nevertheless, there are critical gaps between Nepal’s women-friendly laws and the real-life discrimination still rife in local governance and natural resource management.

Solutions: Foster partnerships with intermediary organisations to pool data, advance advocacy and accelerate women-friendly green initiatives

Respectful partnerships with intermediary organisations are also helpful in effecting the shift and getting resources into the hands of women and community groups that need it.

Partnerships and alliances are vital with intermediary organisations that:

- can provide political, media and public profile for women-led and gender-relevant green economy issues including, where necessary, pressure for policy change

- can pool data and coordinate learning and strategy development among different women’s organisations, enterprises

- can provide conduits to financing by mobilising connections that grassroots women’s organisations and small enterprises would not otherwise access (including literal translation of materials among languages where required).

Direct partnerships and alliances with investors in women-led, women-dominant and women-relevant initiatives are helpful when external investors are respectful and led by local women’s priorities.

An example of a highly effective intermediary organisation is the Bolivian Observatory of Sustainable Tourism (Observatario Boliviano para el Industria Turística Sostensible – ORBITA), founded by the GLOW project Tourism as an engine of gender-inclusive and sustainable development in Bolivia. Its purpose is to transform Bolivia’s economy from reliance on traditionally male-dominated, extractive economic activities to more gender-inclusive and environmentally-sustainable activities, grounded in Bolivia’s rich natural and cultural assets.

ORBITA had many successes. During the initial set-up phase:

- It researched the potential of tourism as an engine for gender-inclusive and sustainable development; gender gaps and gender issues in the tourism industry; major concerns, needs, requests and recommendations from different parts of the Bolivian tourism industry during the pandemic; the environmental footprints of Bolivian tourism. ORBITA further sponsored 25 students to undertake Masters theses on women’s economic empowerment in eco-tourism.

- It provided business advisory services to women-led and women-dominated tourism enterprises.

- It built partnerships and alliances to consolidate and capitalise on Bolivia’s potential as an eco-tourism leader.

These initiatives together culminated in the production of the flagship report “Tourism with a Purpose and the 2030 Agenda in Bolivia” (available in Spanish as “Turismo con Propósito y la Agenda 2030 en Bolivia”). The report demonstrates that tourism has the potential to become the main export product of Bolivia in just 5–6 years, generating much-needed foreign currency revenues and hundreds of thousands of high-quality jobs, especially for women and young people, with minimal environmental harm. This can be achieved in Bolivia if five particularly beneficial types of tourism (cultural, adventure, community, gastronomic and scientific) are prioritised to unleash this potential.

With these ideas, ORBITA was supremely successful in capturing the political and public imagination during the economic recovery from Covid-19 and in the context of further external shocks to the Bolivian economy. The office of the Vice Presidency asked the project to turn the recommendations into a Supreme Decree to achieve real and rapid impacts.

The team produced a draft decree, currently in the hands of the Vice President of Bolivia for approval. Their efforts to promote tourism as an engine of sustainable and inclusive development have also been recognised by the Legislative Assembly, with awards to both ORBITA and SDSN Bolivia. But how to bridge from this vision and commitment to gender-responsive, low environmental impact and profitable tourism, to realising it on the ground?

The team developed a multi-pronged sustainability strategy to bridge this vision and emergent policy into a practical and sustainable pathway for implementation. Based on an analysis of supply, demand, and opportunities, ORBITA’s future actions can be framed in four areas for which funding will be sought. Again, the importance of ORBITA is evident for women-led and women-dominated tourism enterprises, as well as for aspiring women leaders. ORBITA acts as an intermediary organisation with catalytic potential to mobilise cooperative agreements and funding in the following domains:

- Working with universities: This ORBITA programme aims to channel resources to deepen research and connect local researchers with international ones. By doing so, it also aims to promote Bolivia as a tourist destination in other countries. In addition, ORBITA has managed to convince the Chancellor of Universidad Privada Boliviana – UPB that tourism is the future for Bolivia. As a result, UPB is presenting its new bachelor’s programme in Hospitality to the Ministry of Education for approval 22

- Working with subnational governments: This programme aims to provide research services, territorial development, and public policy development for municipal and departmental governments, using the ORBITA platform to showcase data and tourism offerings.

- Community tourism enterprises: This ORBITA programme seeks to develop community tourism in Bolivia, promoting the participation of local communities in the sustainable management of their natural and cultural resources.

- Business advisory services: This ORBITA programme aims to provide a comprehensive service that offers up-to-date sectoral information, personalised advice, and high-level management training to strengthen the strategic positioning, competitiveness, and effective decision-making of tourism companies in Bolivia. 23

In Nepal, where we have noted the large gap between gender equality policy and implementation, the Southasia Institute for Advanced studies under Co-producing a shock resilient business ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal has flexed its capabilities as a convening organisation to bring together members of communities, local governments, and national level institutions. SIAS has specifically convened these stakeholders to reach a common understanding of why gender equality and social inclusion are not being realised in the implementation of climate-smart agriculture policies. A 2023 policy roundtable focused on:

“the lack of or distorted policy implementation and its failure to cultivate expected outcomes for women’s economic empowerment, even when policy provisions on paper are positive in terms of gender equality and social inclusion. Insights received from the experts demonstrated that the challenges posed from inadequate policies, not harmonised regulatory instruments, lack of capacity to implement policies, lack of sufficient budget, techno-bureaucratic apathy, politics of local development, and attitude of the politicians, bureaucrats and other actors.” 24

The project has responded to the constraints identified by organising further deliberative dialogues, formal and formal meetings with local stakeholders involved in women’s market access for their sustainable produce, as well as trainings for women producers and government officials to unlock localised solutions.

Action research approaches have been the foundation for capacity development and change processes for most GLOW grantees, who hail from think tanks, universities, NGOs and consultancy organisations and act as intermediaries. (Similar action research approaches are sometimes referred to as ‘co-production’ processes or ‘knowledge brokering’.)

Simply put, these approaches regard community-based women, including entrepreneurs, and local government officials as members of the broader research team that together co-investigates the drivers, barriers and solutions for women’s empowerment and climate action.

These different actors have typically gathered and analysed data together, to establish a ‘situation analysis’ or baseline, and they have co-developed tailored interventions for specific localities and businesses. In the case of intensive and time-heavy data collection processes, such as household surveys, the work has fallen to the GLOW grantees; later the community-, government- and enterprise-based participants on the team have come in to co-analyse the evidence and develop recommendations and actions.

The added value of the intermediary organisations is their resource and skill in contributing technical analysis (on gender and/or climate change mitigation and adaptation), facilitating focus groups and dialogues, and convening stakeholders strategically to inform and accelerate policy decisions and implementation.

These institutions were also the recipients of IDRC funding and handled the fiduciary compliance with the donor, the accounting and financial reporting. Most of them passed on microgrants to community institutions as a form of small but strategic catalytic funding for enterprise start-ups, climate-smart shifts in production systems and the full range of capacity strengthening and peer learning support we have described in this report as being necessary to women’s empowerment.

Solutions: Strengthen the gender capacity of local government personnel

Often, there is a gap in complete understanding among government staff at district, municipal or local government staff on how to implement gender equality policies and, particularly, how to apply them to climate and sectoral actions. These personnel are critical because they are on the frontlines of delivery.

It can be highly effective to run briefings and trainings and/or foster dialogues involving local government officials to support their capabilities for implementation.

For example, in Malawi, the Prioritizing Options for Women’s Empowerment and Resilience in Food Tree Value Chains in Malawi (POWER) project aims specifically to involve district government staff in co-developing activities to empower women in food tree value chains – so that they are vested in the outcomes. The project also intentionally seeks to capacitate district staff on gender issues.

One of POWER’s aims is: “to capacitate targeted end users—the Government of Malawi (through its District Agriculture, Environment, and Natural Resource [DAENR] offices), other implementing organisations, such as NGOs, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and concerned private sector actors, such as Malawi Mangoes and Shire Best—with guidelines, community training and communications materials, policy briefs, and targeted training to action the co-developed intervention and policy options.”

It has held deep dive ‘catalyst meetings’ with district government and agriculture field agents. Designed as part of the gender transformative intervention, these aimed to review the progress of work. It also provides opportunities for POWER trainers, mentors and community participants to reflect and plan together with the district officials.

These check-points also provided a chance for the project to develop the awareness and understanding of local government officials and field agents on the needs and constraints of the local women farmers and their roles in the value chain vis a vis men. 25 The sessions took three days (December 2023), and involved 24 district officials from the two targeted districts.

“Most critical to this methodology was the community engagement approach and feedback learning mechanism that allowed all stakeholders participating in the POWER Model to co-learn and reflect on things that work and might not be working for the success of meaningful women’s empowerment and livelihood improvement.” 26

In Cambodia, GrowAsia has engaged especially with the agricultural extension agencies of local government. It is particularly important that extension agents understand the nature of gender-related barriers to uptake of climate-smart agriculture, because they are the ones who introduce new farming inputs and techniques to women and men in the field.

GrowAsia has recommended strongly that extension agents “are aware of the specific barriers women face, how this inequity negatively impacts all members of the community, and how these constraints can be alleviated”. They also urge local extension agencies to increase women’s access by “holding trainings at times convenient for women, allowing women to attend with their children, or sharing training summaries electronically via a platform that is accessible to women in rural areas (such as Telegram groups which allow for voice and video messaging)” (CPSA and GrowAsia, 2023, page 8.).

In Vietnam, GrowAsia is urging local government personnel to tighten up health and safety measures for women farmers, and to take proactive measures to safeguard their healthcare and mobility needs during agricultural training, on account of “weather, field mud, and chemical materials used in rice cultivation, and also the ageing of women labourers” (GrowAsia, 2023, page 14).

In the Philippines, GLOW researchers are promoting the idea of providing local governments with a ‘local development budget menu’ of women-empowering, low-carbon, climate-resilient agricultural development options, to steer these entities toward more integrated investments.

Solutions: Get funding into the hands of women entrepreneurs

Groups of local women need money to support their activities to bridge the gap between gender equality policy and its implementation, especially in the context of low-carbon, climate-resilient economies.

As discussed earlier, women need resources both for formal and informal activities that nurture their skills, confidence, leadership, product and market development, and that foster dialogue, understanding and moral-practical support among generations, genders, castes and ethnicities in their localities.

While GLOW projects explored the use of pooled funds generated by women themselves, there is also a need for external support to finance a range of business- and livelihood-critical activities, including but not limited to:

- subsidies for inputs and capital costs for entry to low-carbon, climate-resilient markets

- resourcing for women’s collective organising, community convening and policy engagement, including venue, materials and communications costs

- resourcing for training in the diverse dimensions of capability strengthening (such as technical skills, business and financial skills, and leadership coaching).

The GLOW programme did not drill in depth into institutional financing models, but a parallel initiative by Convergence and Climate Policy Initiative is highly germane. They have analysed the gender responsiveness of climate investments, published as Blended Finance and the Gender-Energy Nexus: A Stocktaking Report (August 2024). The analysis is based on Convergence’s Historical Deals Database, which lists climate investments classified as impact investment because they:

- attract financial participation from one or more commercial investor(s) that would otherwise not have invested in the region/sector/project

- leverage concessional capital from public or philanthropic investors, with grant funding and/or technical assistance

- intend to create development impact related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or directly benefit groups in emerging or frontier markets.

On this basis, the study found that 78% of climate transactions are ‘not even gender-aware’. 17% are ‘aware and counting’ and 5% are ‘intentionally gender-focused’. Of the latter categories, most are in the agriculture sector and involve development finance institutions.

This analysis identifies a critical gap and a shift needed by public and philanthropic funders to support women’s low-carbon, climate resilience leadership in emerging and frontier economies.

The importance of gender-responsive budgeting in policies and programmes

Gender-responsive budgeting is a strategic approach to integrating gender perspectives into budgeting and planning processes and supporting activities to enable women and men to benefit equitably. The government of Nepal endorsed gender-responsive budgeting in 2007–2008 and made it mandatory. The local government in Malarani sought the support of the GLOW project Co-producing a gender and shock-responsive ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal to integrate the approach into its annual plan. The project organised gender equality and social inclusion orientation and deliberative forums to sensitise local elected representatives on the policy provisions and benefits of gender-responsive budgeting. This has strengthened the municipal commitment to adopting the approach and led to clearer articulation of target groups by municipal programmes. It has also resulted in increased gender-responsive budget allocations, and a plan for awareness training for other municipal officials and council members.

Interviewing woman entrepreneur with baby, Nepal (c) ForestAction Nepal

Address unpaid work, including care work, as an intrinsic part of climate action

Issues